Amsterdam-Noord experienced a red carpet moment on Wednesday when the Nxt Museum received Marco Brambilla, the director who scored a hit thirty years ago with Demolition Man, a futuristic action film starring Sylvester Stallone, Sandra Bullock and Wesley Snipes.

Amsterdam-Noord experienced a red carpet moment on Wednesday when the Nxt Museum received Marco Brambilla, the director who scored a hit thirty years ago with Demolition Man, a futuristic action film starring Sylvester Stallone, Sandra Bullock and Wesley Snipes.

Since then, the Italian Canadian has made short films, which were shown in Cannes, among others. But he is best known for his large-scale video artworks in which he puts Hollywood through the meat grinder.

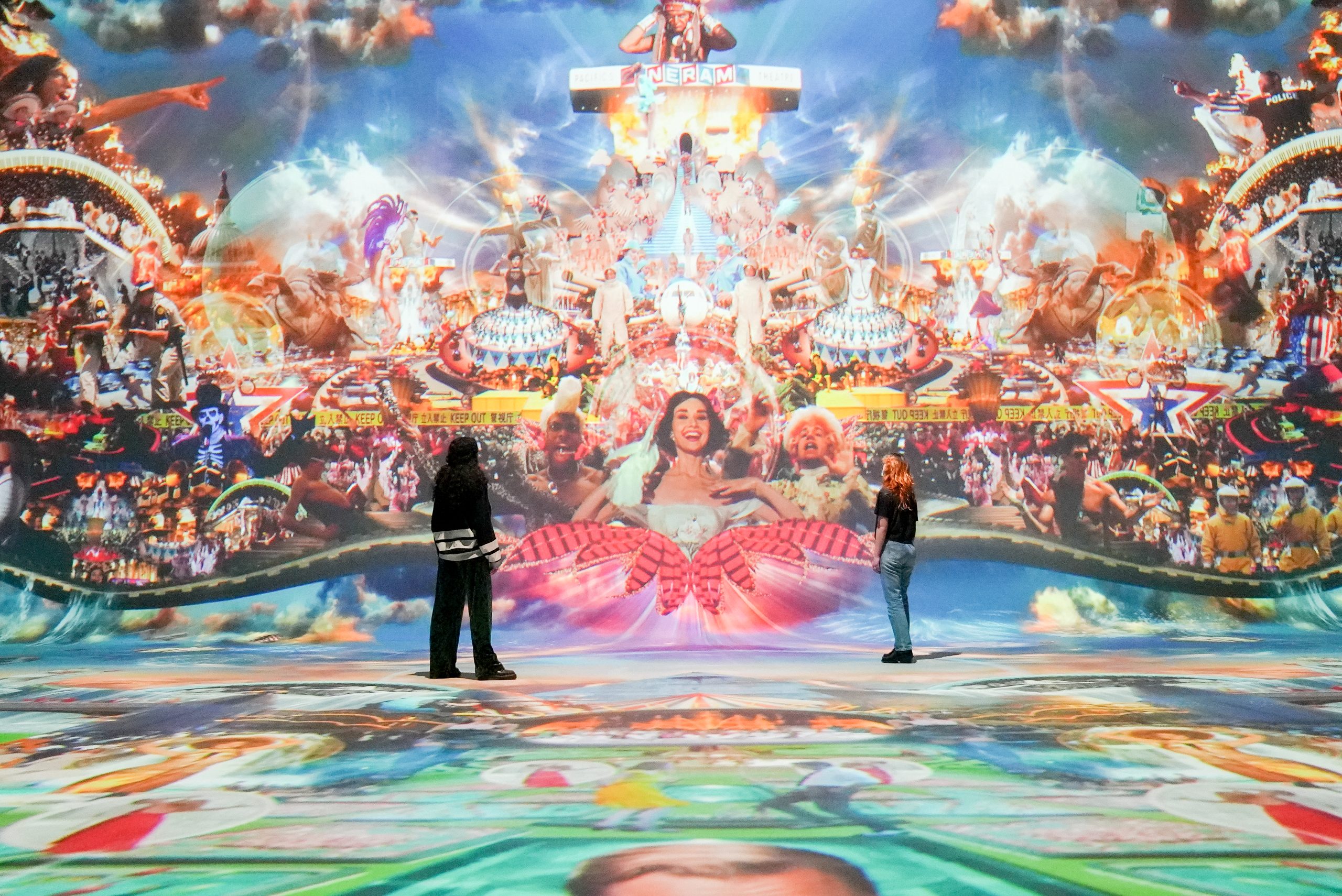

From Brambilla’s four-part series Megaplex, Nxt Museum is showing the last two parts, Creation (2012) and Heaven’s Gate (2021), which have never been shown in the Netherlands before. Visitors are served a cross-section of film history, presented as collages made from fragments of hundreds of films.

Chaplin and Superman

Creation starts with the big bang. Then semitransparent DNA strands float in the primordial soup and bubbles filled with images of what is to come: amoebas, sharks, people. The soundtrack features Cinderella, a lighthearted waltz by Sergei Prokofiev. It is a nod to the much more bombastic An der schönen blauen Donau by Johann Strauss that plays an important role in 2001: A Space Odyssey.

In terms of image, Creation is much more baroque than that science fiction classic in which Stanley Kubrick depicts the development of humanity. Where Kubrick’s 1968 film unfolds at almost walking pace in almost 2.5 hours, Brambilla blasts through the origins, flourishing and fall of earthly life in just four minutes.

Brambilla draws on almost four hundred films, from which he cut approximatelv two thousand obiects and characters. These are incorporated into a slowly circling image, a vortex that sucks the viewer in. The circle of life begins with idyllic meadows, in which Julie Andrews from The Sound of Music, among others, makes an appearance.

Sex should of course not be missing, because when you say creation, you imply reproduction. Don’t expect hardcore porn, though. Brambilla’s sources are mostly decent blockbusters. Because in Hollywood, butchery is seen as less serious than sexual intercourse, the violence at the end is a lot more explicit.

While the explosions and conflagrations from Independence Day and The Towering Inferno burn the world to ashes, Superman flies by with an American flag and Charlie Chaplin dances on the ruins like Hitler from The Great Dictator.

– In Heaven’s Gate the image moves from top to bottom, which evokes associations with the end credits of films.

End of the film author

While Creation drills the viewer through time like a corkscrew, Heaven’s Gate offers a different viewing experience. Here the image moves from top to bottom, which evokes associations with the end credits of films.

These so-called closing credits usually end with the logo of the film studio. That doesn’t happen here, but the title Heaven’s Gate is taken from the western of the same name by Michael Cimino, which bankrupted United Artists in 1980. After this debacle, no studio dared to give free rein to idiosyncratic filmmakers. They were replaced by spreadsheet managers who were fully committed to commercial, risk-free entertainment. Heaven’s Gate marked the end of the ‘film author’ and the beginning of the era in which sequels, prequels and infantile superhero films predominate.

In addition to being a commentary on Hollywood’s decline, Brambilla’s Heaven’s Gate can also be seen as a representation of Dante’s Purgatorio, the second part of the Comedia Divina that leads through the seven layers of purgatory.

It starts with a blazing fire, followed by a gloomy cemetery and an underwater world in which Scarlett Johansson as a mermaid holds sway. On the next level, wild nature reigns supreme with King Kong and the dinosaurs from Jurassic Park. As we ascend to Leonardo DiCaprio raising a glass like The Great Gatsby, the percussion swells. In the finale, police officers march, cowboys swing their lasso and chorus girls dance. This is all put into perspective by the theater beams with spotlights that become visible above them. It’s all show.

Viewer as weak-willed victim

Or as Brambilla himself says: “I celebrate the spectacle by making a spectacle.” By using that term emphaticall. he refers to Guv Debord, who coined the term société du spectacle in 1967 to describe our rapidly evolving visual culture. According to the French philosopher, we are increasingly surrounded by images of reality that seem more real than reality itself. Debord already felt this half a century ago, long before video, the internet and virtual reality. Nowadays there are entire tribes of people for whom life online is more authentic than a trip to the supermarket. And many more people use the Leonardo DiCaprio meme from The Great Gatsby in app contact so that they don’t have to formulate anything themselves.

Brambilla sees his work as a form of entertainment, but the moral is not lacking. By greatly reducing and exaggerating the output of the entertainment industry, he underlines the blinding effect of the parallel universe covered in man-made images. His collages have a seductive compulsiveness that transports the viewer as a weak-willed victim – and keeps them coming back for more. Because Brambilla’s work is so addictive.

With every viewing you are rewarded with even more details, even more aha moments, even more spectacle. But as is the case with every superlative: everything gets used and becomes normal

What Guy Debord found spectacular in 1967, we now find soporific. The question is also how Brambilla, which has always stayed ahead of the mainstream application of technology, deals with this. And how his works will be experienced in ten or twenty years. Still overwhelming or a showcase of early 21st century, now dated technology?

This article originally appeared in Het Parool on 29 February 2024

Author:

Edo Dijksterhuis

Categories:

Press Review

Date:

14 March 2024